Mirimichi Green Launches New Soil Amendment Essential-G

Mirimichi Green Launches New Soil Amendment Essential-G™

06/09/2020 – Castle Hayne, NC – Mirimichi Green has expanded its granular product line with a new, prilled soil amendment called Essential-G. Essential-G contains the most essential components for amending the soil in a uniquely spreadable granular format.

Underpinned by Mirimichi Green’s CarboMatrix technology, Essential-G is comprised of silicon, reclaimed coffee grounds, premium composts, humates, and USDA Certified Biobased Carbon (biochar). Each of these ingredients has proven field research and test results demonstrating effectiveness in improving soil health and quality, but they’ve never been available in a single, convenient product.

Essential-G’s consistency is ideal for spreading in any standard push-behind spreader. After months of field testing, the size of the prill goes out easily with no agitator or additional equipment needed.

To get more information about Essential-G and view application rates, click here.

Essential-G can be used for all residential and commercial turf establishments, new seed, sod, and planting applications. Some of the benefits of Essential-G include:

- Strengthens root growth

- Aerates soil and reduces compaction

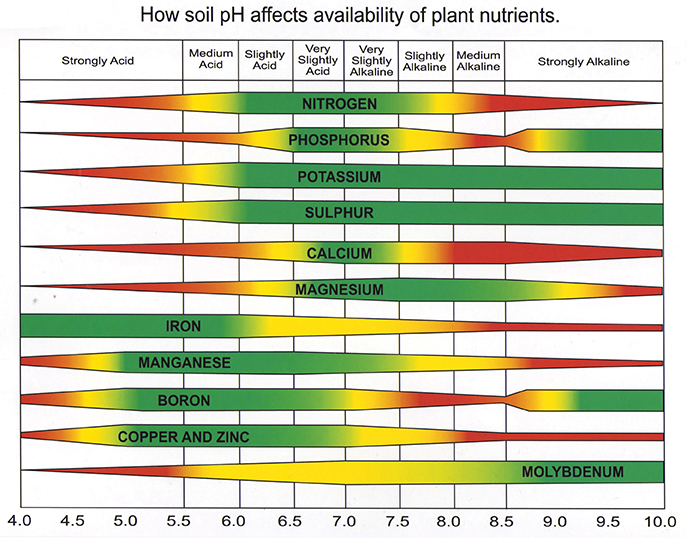

- Optimizes pH

- Increases water holding capacity

- Increases nutrient uptake (CEC)

- Long-lasting biochar increases residual value

- Promotes natural chelation of Iron

- Adds essential organic matter for microbes

- Provides fast green-up and recovery

Mirimichi Green is constantly researching and testing new ingredients to bring customers the best and most effective products on the market. In early 2020, Mirimichi Green partnered with Sigma Agriscience and started developing Essential-G by combining new technologies and proven soil amending inputs. Both companies are excited to bring this product to the market and see end-users soil health improve.

Learn more about Mirimichi Green and Sigma AgriScience, LLC’s partnership here.

Start incorporating Essential-G into your turf maintenance and installations to achieve optimal soil health.